Opcode Glossary

The following section is meant to be skimmed once and then used as a reference. You don’t need to memorize everything in here right off the bat.

You’ll probably want to book this handy-dandy reference: THUMBREF. It shows all the opcodes that you’ll have access to in thumb mode, along with how to use them, albeit in a shorthand that may seem intimidating to a beginner. That’s where this section comes in. I’ll explain things in more detail and include a few tips and tricks.

Rather than being organized in alphabetical order, the opcodes are grouped by similarity.

Stack manipulation: push, pop

Writing a function, any function, almost always begins with a push and ends with a pop/bx combo. Push copies the contents of the register(s) onto the stack, in descending order, and decrements the stack pointer by 4 (since each register is 4 bytes in size) as it goes.

Example: push {r4-r7,r14} copies r14 to the stack, then r7,r6, r5, and r4, in that order, and subtracts 4*5 = 0x14 to sp (the stack grows downwards, see the Stack Viewer in the no$gba overview section for an explanation).

Pop is basically the opposite. It copies the topmost value to from the stack to the register in the argument, and increments sp by 4.

Example: pop {r4-r7} copies the first value on the stack to r4, the second value to r5, third to r6, and fourth to r7. Notice how that’s the same order that we ‘pushed’ earlier.

Why didn’t we pop into r14, you ask? Because we’re not allowed to. You can pop into r15, but there are a couple of reasons we don’t:

- It doesn’t work if you’re returning to ARM code. While this will basically never be an issue, it’s still good to keep in mind.

- It doesn’t allow you to tell at a glance whether a function returned something or not. See the “Branchs” section for more info.

The arguments for both are surrounded by curly braces. You can use a dash to indicate a range, or separate registers with commas, or both, as in {r1,r3-r4,r6,r7}. The order doesn’t matter; {r1,r2} is the same as {r2,r1}, although using the former is recommended for readability.

Notes:

- Always, always, ALWAYS pop as much as you push. If you don’t, you’ll probably mis-align the stack, and that will almost certainly make your game come to a screeching halt. Literally, in some cases.

- A common misconception is that

pop {r4}, for instance, puts the value that used to be r4, back into r4. This is not true. Pop just takes the top value from the stack. There’s no way for the code to “remember” where a value came from; that’s on you to ensure everything goes back in the right place. - If you’re writing a function, and you want to use r4-r11, you’ll have to save their values via push/pop. Don’t assume just because a register’s value is 0, that means it’s not being used.

- Continuing that thought, you can’t push or pop the higher registers directly (push r14 and pop r15 being the exceptions). So if you want to save r8-r11, for instance, you’ll have to do something like this:

push {r4-r7,r14}

mov r4,r8

mov r5,r9

mov r6,r10

mov r7,r11

push {r4-r7}

<rest of code here>

pop {r4-r7}

mov r11,r7

mov r10,r6

mov r9,r5

mov r8,r4

pop {r4-r7}

pop {r1}

bx r1

There’s a few opcodes that you haven’t been introduced to yet. ‘mov’ copies the contents of one register to another, and bx…well, see the Branches section.

So what does this do? Well, first we save r4-r7 and r14 with the first push. Next, we copy the higher registers’ contents into r4-r7, which we’re allowed to do because we already preserved their original values, and we push those. When it comes time to end the function, we do the same in reverse: pop what was in r8-r11 in a lower register, copy them to the higher register, and finally pop the original values.

Comparisons and branches: cmp, cmn, b, bl, bx

There are 3 different kinds of branches available to us, each with their advantages and disadvantages. The first is b, which is an unconditional jump, or goto. Pretty simple to use and understand. There are also conditional branches, such as beq, bne, bge, etc. These are equivalent to if/then statements.

B

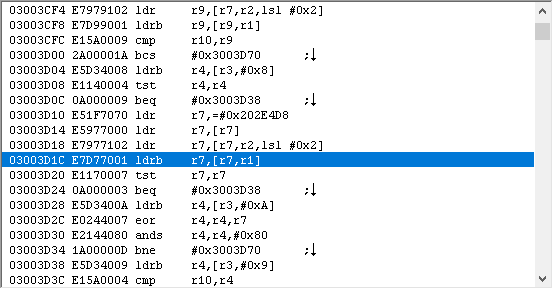

A conditional branch is always preceded by a cmp, or compare. Cmp can either compare a register to a byte-sized constant (cmp r0,#0xFF), or compare 2 registers (cmp r0,r1). If the latter, at least one of the registers must be a low one.

Cmp works by subtracting the right argument from the left one, so cmp r0,#0xFF will do r0 - 0xFF, and then sets the 4 status flags next to the register list (negative, zero, carry, and overflow). (Technically c and v are both overflow flags; c is for unsigned overflow and v is for signed overflow, but you don’t really need to understand how the flags work to use cmp).

Cmn is compare negative, and works almost the same, except cmn r0,#0xFF would calculate r0+0xFF and set the flags accordingly. I have never used it, never seen it used, and completely forgot about its existence until I wrote this guide, but I’m mentioning it for the sake of completeness.

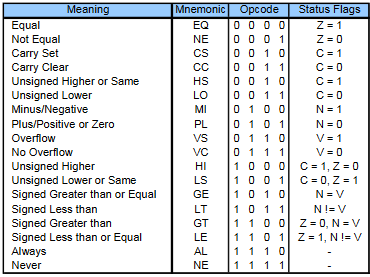

Once the flags are set, you can use them to do the following conditional branches:

It should be noted that while conditional branches are the only opcodes that use the flags, several others other than cmp and cmn can set them.

The last column has x’s indicating which flags an opcode can set. For this reason, it’s recommended to keep your compares and conditional branchs close together. There’s no reason not to, and it makes your code easier to read. And while you can use opcodes other than cmp to set the flags, I’d say you shouldn’t unless you absolutely really positively need the space that a cmp would take, just for the sake of readability.

BL

bl, in contrast to every other thumb opcode, is 32 bits. This is because it’s basically 2 opcodes in 1, a branch and a link. bl is the equivalent of a function call. The code that’s currently being executed is put on hold, we jump to another location, execute code there, and return back when done.

In order to return, we need to know the address that we jumped from. This address (+4/5, see bx) is stored in r14, which is also called lr, or the link register. To ensure the address is saved, the first thing the function being called will do is push r14. Otherwise, if the function being called has its own function calls, the new address to return to will overwrite the previous one, and bad things will almost certainly happen. The exception to this rule is if the function is very short and is guaranteed to not have any function calls; if that’s the case, you can leave r14 alone (although there’s nothing wrong with always pushing it).

The syntax is quite simple: bl 0x8019430, for example.

BX

bx is also an opcode that does 2 things at once, but unlike bl, it’s a standard 2-byte opcode. bx stands for branch and exchange. The branch part is easy. You put the address you want to go to in a register, say, r0, then bx to it: bx r0.

But wait. What are we exchanging, you ask? Well, remember way back in the beginning, I explained that the game contains both thumb and arm code? Sometimes, we need to switch from one to the other. That’s where the exchange part comes in. How does the processor know when to switch? If the first bit of the address to jump to is set (ie, address is odd), the code will be in thumb mode. If it’s not set, the code will be ARM. Pretty simple. If you’ve done any eventing and had to use ASMC, and had it drilled into your head that the address of the asmc has to have 1 added to it, this is why. If you don’t make it odd, the code will be executed in ARM mode, and, well, almost certainly won’t work.

While b and bl have constraints as to how far they can go (see comparisons), the fact that bx loads the address in a register means it has no such constraint. You can go anywhere with it.

If you’ll recall from the push/pop section, I pushed and popped a bunch of registers. Amongst those, we pushed lr in the beginning, and then the last two lines were pop {r1}, bx r1. lr, you’ll recall, contains the address we need to return to after this function is finished. We can’t pop it directly into r14, and we don’t like to pop into r15, so we put it in a lower register, and the bx to the address. bl adds 4 to the address to skip the bl command itself (we don’t want to execute the bl again, otherwise that would result in an infinite loop), and then adds 1 if the code to return to is in thumb mode, for a total of 5.

Convention dictates that if the function returns a value, you use r1 to bx back, and if it doesn’t, use r0. This allows you to tell at a glance whether a function returns something or not. It’s recommended that you stick to this convention, although you don’t have to.

Comparisons

b: The unconditional branch is 2 bytes long, and has a max range of +/- 0x3FF bytes.

b <cond>: The conditional branch is also 2 bytes long, but only has a max range of +/- 0xFF bytes, due to needing space for the conditional type.

bl: branch and link is 4 bytes long, and has a max range of +/- 0x3FFFFF bytes.

bx: branch and exchange is technically 2 bytes long, although it needs the target address to be loaded in a register, and has no limits as to how far it can go.

That’s nice to know and all, but when should you use what?

b and its variants should be used only within a function.

bl is used for function calls. There is one exception: if the function is so long that even b won’t work, you can use bl as a branch and just ignore the ‘save the link register’ bit. I believe there’s only 2 functions in FE8 that are long enough to require this.

bx is used for returning from a function call, for jumping out of bl range (this will be used a lot), and for exchanges between thumb and arm code.

Unary and binary bitwise operators: mvn, neg, and, orr, eor, bic, tst

The following instructions are easier to visualize with numbers in a binary representation, so all numbers are in base 2. They’re also separated into groups of 4 digits so you can read them easier. Remember that a byte is 8 bits.

A unary operation is an operation that only takes 1 input. Our instruction set has 2: mvn (move negative) and neg (negate). Despite sounding similar, they’re not quite the same.

mvn is more commonly known as “not”, as in “not A” or “!A”, or as taking the “one’s complement”. Given a number, you toggle each bit. If the bit was set, unset it (1 becomes 0); if it was unset, set it (0 becomes 1).

@r0 = 1010 1101

mvn r1,r0

@r1 = 0101 0010

Notice that if you sum r0 and r1, you get 1111 1111, or -1 (if the number is signed).

neg is also known as taking the “two’s complement”. As the name suggests, you’re just negating the number. 1 becomes -1, 3 becomes -3, -20 becomes 20. The easiest way to do this is by taking the one’s complement and adding 1.

@r0 = 1010 1101

neg r1,r0

@r1 = 0101 0011

As you might expect, summing r0 and r1 will equal 0.

Binary operations, as the name might suggest, take 2 operands, or inputs. For the following, r0 = 1010 1101 and r1 = 1100 0101.

The operation looks at bits in the same position in the two inputs and creates a new number with the results, which replaces one of the operands: and r0,r1, for instance puts the result in r0.

and: Also represented with &. A bit is set (1) only if it is set in both inputs.

1010 1101

1100 0101 &

1000 0101 =

orr: More commonly known as or, or |. A bit is set (1) if it is set in one or both inputs.

1010 1101

1100 0101 |

1110 1101

eor: More commonly known as xor, “exclusive or”, or ^. A bit is set (1) if it is set in one input or the other, but not both.

1010 1101

1100 0101 ^

0110 1000

bic, or bit clear, is a combination of mvn +and.

bic r0,r1

is almost equivalent to

mvn r1,r1 and r0,r1

In other words, it clears the bits that r0 has in common with r1. The difference between those two examples is that bic would not change the value in r1.

1010 1101

1100 0101 bic

0010 1000

Note that order matters! 1 bic 0 is 1, but 0 bic 1 is 0. If this weren’t the case, bic would be identical to eor.

I’ve never seen this used in vanilla FE8 code. The compiler seems to prefer a neg/and combination.

tst, or test, is a combination of and + cmp (register), #0x0.

tst r0,r1

is almost equivalent to

and r0,r1 cmp r0,#0x0

The difference is that the value in r0 is untouched. It’s useful if you need to know whether a bit is set, but don’t care about the value obtained when using and (which is most of the time).

Loads + mov: mov, ldr, ldrb, ldrh, ldsb, ldsh, ldmia

These opcodes are for putting a value into a register, or dereferencing memory (getting data at an address).

mov stands for “move”. There’s 2 ways to use it.

mov r0,#0xFF puts the value 0xFF into register r0. The argument must be 1 byte.

mov r0,r1 copies the value in r1 into r0. Nothing happens to r1, so it’s not exactly moving here, but whatever.

That’s it. Pretty straightforward, no?

Now let’s look at the dereferencing stuff.

ldr stands for load register. With what, you ask? That depends on the following letter:

b = byte: ldrb

sb = signed byte: ldrsb, which is shortened to ldsb

h = halfword: ldrh

sh = signed halfword: ldrsh, which is shortened to ldsh

if there’s no letter, than load a word

Ok, now where are loading from? That’s defined in the arguments.

Example: ldr r0,[r1]

The brackets indicate deferencing: “Go to the address in r1, retrieve the word at that location, and put that value in r0.”

But we can also get a bit more complex by throwing in a non-negative constant:

ldr r0,[r1,#0x4]

Same as the above example, except we’re retrieving the word at address [r1+0x4].

We could also put the constant into another register:

mov r0,#0x4 ldr r0,[r1,r0]

and this will yield the same result as example 2.

Now, there’s a couple of things you should know:

- If you’re using the second method, there’s 5 bits set aside for the constant. That means in

ldrb [r0,r1,X], X must be less than 32 (0x20).ldrhandldrmultiply this value by 2 and 4, respectively, meaning you can load stuff further away, but also means you cannot load values that aren’t 2- or 4- aligned.ldrh r0,[r1,#0x2]will work fine;ldrh r0,[r1,#0x3]will not. -

ldsbandldshwill not work with method 2 at all. If you want to use that constant, you must load it into another register first. Even if the constant is 0.ldsb r0,[r1]will not work.

That second point might make you ask, what exactly is the point of usingldsboverldrb? That’s best illustrated through an example. Let’s let the value at the address in r1 be 0x7F. Thenldrb r0,[r1](which is equivalent toldrb r0,[r1,#0x0]) will put 0x0000007F into r0, which is the same as 0x7F.

We can’t ldsb directly; we have to put the constant into another register first.

mov r0,#0 ldsb r0,[r1,r0]

This also puts 0x0000007F into r0, because 0x7F doesn’t have the top bit set, so it’s not a negative number. In this instance, the two opcodes have the same result.

Now instead, let’s put 0x80 at that location.

ldrb r0,[r1]will still yield r0 = 0x80. Nothing new there.

ldsb, using the same code as above, will see that the byte loaded does have the top bit set, indicating that it’s a negative number. But that’s a byte, and the register we’re loading into is a word (4 bytes) long. Whatever will we do? Extend the sign by setting all the bits in front of (to the left of) that byte. So now 0x80, as a byte, becomes 0xFFFFFF80, as a word.

Ldrh vs ldsh is the same. Let the example value be 0x8000; then ldrh will yield r0 = 0x00008000, and ldsh will yield 0xFFFF8000.

You might notice that there’s no “load register with signed word”. Why? I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

Remember how mov can only put a value that’s a byte long into a register? If you want to put something larger, and you will, you’ll also need to use ldr as follows:

ldr r0,Deadbeef <code> .align 4 Deadbeef: .long 0xDEADBEEF

You put the value in a constant pool or literal pool, and then use ldr to dereference [pc + constant] and retrieve the value. Or in other words, since we can’t fit the argument (0xDEADBEEF, 4 bytes) into a 2-byte opcode, we tell the game how far ahead it needs to look to find the argument. The .align 4 is because your literals must be word-aligned.

Notes:

- You must load a word. You can’t do

ldrh r0,Beefor something like that. At least, not directly. You could doldr r0, Beef, where Beef is defined as.long 0x0000BEEF. - The literal must be after the

ldropcode. - You can dereference the stack using r13, but must load a word; eg

ldr r0,[sp,#0x4]. If you only wanted to load a byte, you’d have to do something like

mov r0,r13

ldrb r0,[r0]```

- Remember how the constant in, say, the above example has to be non-negative? This is why having the stack grow downwards is useful. The top value has the smallest address, so you add a non-negative constant to retrieve earlier values.

Finally, there's `ldmia`, or **l**oa**d** **m**ultiple, **i**crement **a**fter. It's not an opcode that you'll use very often (probably), but the syntax is a bit weird, so here's an example:

`ldmia [r1]!, r0, r2-r3`

r1 contains an address which we are loading from, and r0, r2, and r3 are the registers we are loading to (that's the multiple part). We load the first word into r0, then add 4 to r1 (increment after), load the second word into r2 and increment r1 by 4 again, and finally load the third word into r3 and increment by 4. The command is usually followed by `stmia`, which will be covered in the next section. You usually see it used to copy a table from the ROM to the stack (unnecessarily, in my opinion, but that's neither here nor there).

Stores: str, strb, strh, stmia

As you might expect, stores are the complement to loads. Rather than loading to memory, you write to it.

str r0,[r1] stores the entirety of r0 into the address in r1

strh r0,[r1,#0x4] stores the bottom 2 bytes of r0 into the address in r1+0x4

strb r0,[r1,r2] stores the bottom byte of…well, you get the point.

Example: if r0 = 0xDEADBEEF, strb r0,[r1] will write 0xEF to the address in r1. r0 isn’t affected in the process.

stmia is identical to ldmia, aside from the obvious: store multiple registers, increment after. If you think about it, push is essentially stmia exclusively for r13.

Integer operations and shifts: add, sub, mul, lsl, lsr, asr, ror, adc, sbc, adr

Add stands for addition.

add r0,#0xFF should be fairly obvious

add r0,r0,r1 stands for r0 = r0 + r1. If the destination register is omited, it’s assumed the first register is the destination. So we could instead write this as add r0,r1.

add sp,#-0x4 This is how you allocate space on the stack. Notice the minus sign, because the stack grows downwards! To deallocate the space at the end of the function, add it back without the minus sign.

Sub stands for subtraction.

sub r0,#0xFF Again, obvious.

sub r0,r0,r1 Same as addition. Note that while the register order doesn’t matter in addition (add r0,r0,r1 and add r0,r1,r0 are the same), it does matter when subtracting.

While thumbref does say that there’s a sub sp,#constant, I haven’t managed to make it work. So just stick with adding a negative number to r13 for your allocation needs.

Mul is the first one that isn’t as obvious. You can only multiply 2 registers together; you cannot multiply a register and a constant. mul r0,r1 will multiply r0 by r1 and put the result in r0.

lsl = logical shift left

lsr = logical shift right

asr = arithmetic shift right

These are all shifts (no way, really?). In decimal mode, it’s very easy to multiply or divide by powers of 10, right? You just shift the decimal point over to the left or right and add zeroes as necessary. In binary, it’s very easy to multiply (lsl) or divide (lsr) by powers of 2.

@r0=0010 1110b

lsl r0,r0,#0x1 @shift to the left by 1, akin to multiplying by 2^1 = 2

@now r0 = 0101 1100b

lsr r0,r0,#0x2 @shift to the right by 2, akin to dividing by 2^2 = 4

@now r0 = 0001 0111b

Similar to add and sub, if the destination register is the same as the argument, you can omit it: lsl r0,#0x1 is the same as lsl r0,r0,#0x1

Notice that if whatever is shifted outside the register is ‘chopped off’, or truncated. This can be useful:

@r0 = 0xDEADBEEF. We would like to isolate the BEE part.

lsl r0,#0x10 @shift 16 places to the left

@r0 = 0xBEEF0000

lsr r0,#0x14 @shift 20 places to the right

@r0 = 0x00000BEE

asr is similar to lsr, but with a key difference: if the top bit is set prior to the shift (ie, it’s a negative number), then the sign is extended.

Let r0 = 0x80000000

lsr r0,#0x18 would yield r0 = 0x00000080

asr r0,#0x18 would yield r0 = 0xFFFFFF80

You’ll often find code that looks something like:

ldrb r0,[r1] lsl r0,#0x18 asr r0,#0x18

This is called casting an unsigned byte into a signed one. In this example, you could achieve the same result using ldsb (see loads), but that requires at least 2 free registers; 1 to hold the address and the other to hold the constant. If you only have 1 free register, this is an appropriate substitution.

Something you’ll encounter fairly often is that FE’s compiler doesn’t particularly like using mul when it doesn’t absolutely have to. An example is loading item table data. Each entry is 0x24 (36d) bytes long. Given an item id, you can retrieve its data by multiplying the item id by 0x24 and adding that to the table pointer, eg

@r0 = item id

mov r1,#0x24

mul r0,r1

ldr r1,ItemTable

add r0,r1

Which puts the beginning of that item’s data in r0. Here’s how the compiler chooses to implement it:

@r0 = item id

lsl r1,r0,#0x3 @shift by 3, which is the same as multiplying by 2^3 = 8

add r0,r1 @add that number to itself, which is the same as multiplying by 8 + 1 = 9

lsl r0,#2 @shift by 2, or multiply by 2^2 = 4, 9 * 4 = 36 = 0x24

ldr r1,ItemTable

add r0,r1

Instead of using mul, we use a combination of shifts and adds. This actually does end up being faster, at the expense of 1 more opcode, but space is cheap. On the other hand, the time saved is fairly minuscule in the grand scheme of things, so don’t feel bad about using mul. Just watch out for overflows if you’re multiplying big numbers.

ror, or “rotate right”, is similar to shift. Rather than chop off the bits that are outside the register, however, ror inserts them at the other end.

@r0 = 0xDEADBEEF

@r1 = 8

ror r0,r1

@r0 = 0xEFDEADBE

I’ve never seen this used and cannot fathom when you would need to, but, hey, now you know that it exists. Also, it’s another fun one to say. Let me hear you ROR! No? Just me? Ok then. Moving on!

adc (add with carry) and sbc (subtract with carry) are similar to their normal counterparts add and sub, except they bring the carry flag into the mix. I’m not entirely sure how these work, and have never seen them used.

adr, you might notice, doesn’t actually appear in thumbref. That’s because it’s a special form of add; namely, add reg, pc, #. It’s kind of like using ldr to load a literal, except without actually dereferencing the address. It just loads the address into the register. I’ve used it exactly once as of this writing.

Now, you might be wondering why I talked about add, sub, and mul, but there’s no div. That’s because division is actually kind of hard if you’re not dividing by a power of 2 (if you are, just use lsr). You have 3 options:

- Meander over to the Software Interrupts section, which does have a

divfunction - Call the function (FE8: D18FC), which is basically a thumb version of #1 (according to Zahlman)

- Approximate by finding a fraction approximately equal to what you want to divide by, with the denominator being a power of 2

Example: Let’s say I want to divide by 5. Well, 1/5 is equal to 13/65, which is a teensy bit smaller than 13/64. So you could multiply by 13 and right shift by 6 (same as dividing by 2^6 = 64). Is this actually faster than option 1? I haven’t the faintest idea. Again, see SWI.

Software interrupts: swi

There’s only one opcode in this section, and it’s in the title: swi. Think of it as a function call, like bl, except it calls a function that resides in BIOS (the 00 memory block), and is part of the GBA hardware, rather than contained in the cart data. Which function is called depends on the parameter: swi 0x6, for instance, calls Div (divide). You can find out more about the different functions here.

Spacers: nop

nop, or no op(code), is used when you just want to write out some code and are too lazy to use a branch to skip it. It does nothing. It’s actually mov r8,r8, which you may also recognize as doing nothing. Another appropriate spacer has the hex code 00 00, which is lsl r0,r0,#0, and this again, does nothing. Although nop is fun to say.

ARM opcodes

Arm opcodes are, for the most part, nearly identical to their thumb versions, albeit with loosened restrictions (you can use the high registers whenever you’d like) and some extra features (can incorporate shifts and flag-setting in the same opcode for free).

I know the -s ending means “set flags”, but other than that I never had to mess with ARM code. And hopefully, you don’t either.